For the past three and a half months, we’ve been privy to a view of Mintlify (a SaaS company that sells pretty-looking docs) that we don’t know if anyone else outside of the company has seen. Specifically, we’ve been monitoring the code changes to Next.js app that underpins their docs. But how did we get here? And why are we mentioning it now? Let’s start from the beginning.

Note

Everything here was done with only the code that Mintlify already gives its users.

Beginning

As mentioned previously, Mintlify’s offering is that they host your documentation for you, with a focus on AI functionality. It was born after two product pivots by a duo who got into Y Combinator and who came into the whole thing wanting to make a startup.

In a now-deleted Reddit post posted on June 3rd, 2022, they announce that Mintlify had gone open source. A comment on that post points out that the license, the “Mintlify Enterprise license,” makes it source-available rather than open source, meaning it fails to grant certain rights to their contributors. Less than a year later, in February or March of 2023, they reneged on publishing the code and privated the repos, taking on their current SaaS model.

Alyxia was there when this privatization happened. She liked Mintlify—it was pretty, and its approach to components was better than any other documentation tool out there—but she wasn’t interested in a cloud offering; she wanted to keep using it locally. She attempted to make static builds of Mintlify projects, with varying degrees of success. The only approach that ended up working was taking the last client version with available source code (a very old version) and reimplementing interesting newer features on top of it. Alyxia had talked to me about these efforts, and I had poked around a little myself, but in early May of this year, I decided to take another look.

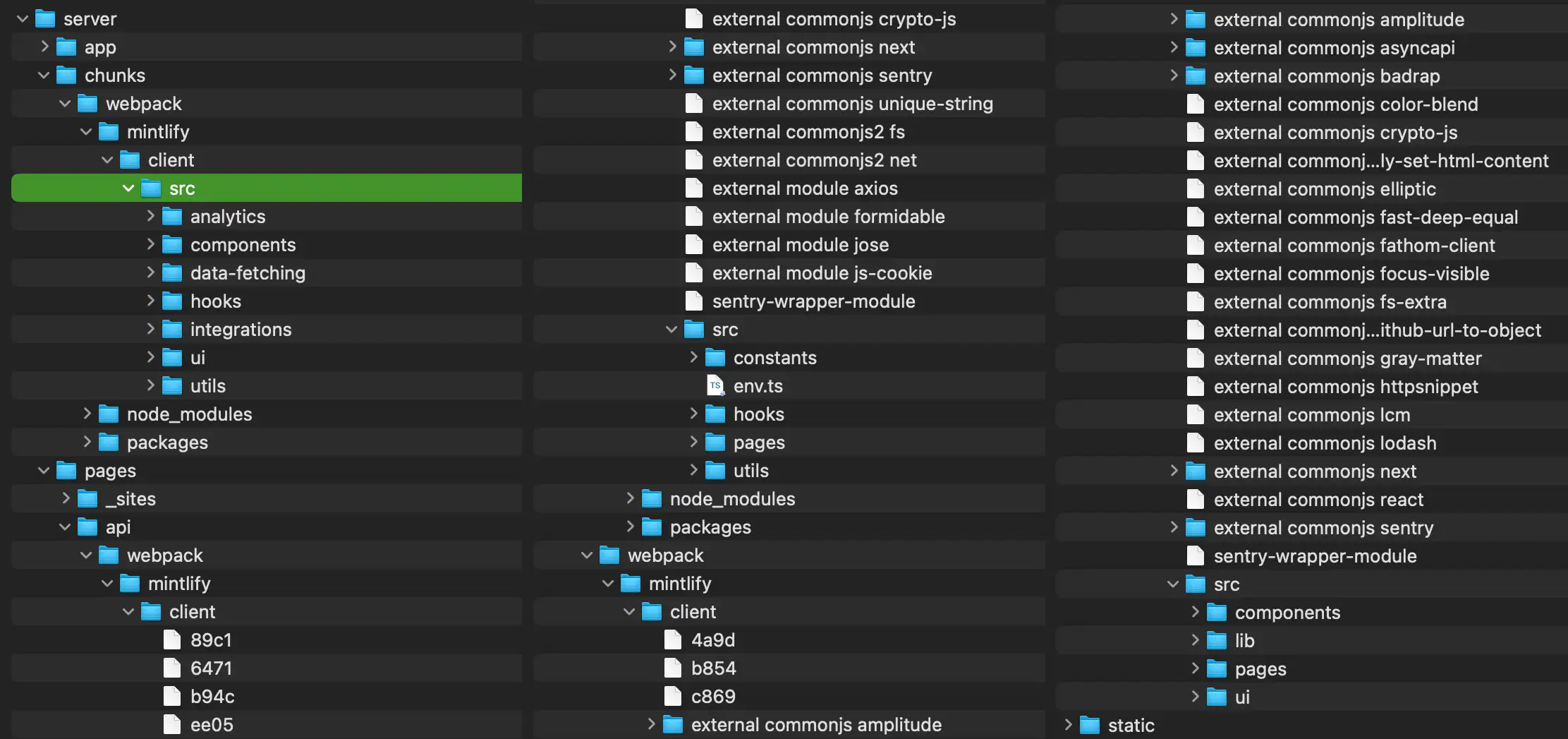

While the actual building and hosting of your documentation is done on Mintlify’s cloud platform, they allow you to preview your docs locally with their CLI, published under the mint and mintlify npm packages (which are identical apart from names and versions). The way it works is that they publish part of their monorepo—a few packages, some projects, and the compiled version of their Next.js client (the .next folder)—in tarball form to their CDN. The CLI downloads and extracts this tarball, then imports Next.js internals to start a dev server, which allows you to view your docs locally. For some reason, the Next.js dev server seems to work just fine when only given the .next folder, but trying to build it fails. In this way, Mintlify can publish their client in such a way that you can only run a local “preview,” but can’t actually make a build.

After taking a closer look at the contents of the tarball, I realized that they had source maps in the .next folder. I wasn’t familiar with source maps or how they worked, but I knew there were projects out there that could use them to recover the original source code, so I decided to give them a try. I ran shuji on the .next directory, and lo and behold:

// server/chunks/webpack/mintlify/client/src/ui/Background.tsx

'use client';

import { DocsConfig } from '@mintlify/validation';

import { ReactNode, useContext } from 'react';

import { DocsConfigContext, PageContext } from '@/contexts/ConfigContext';

import { convertColorsToRgbWithCommas, useColors } from '@/hooks/useColors';

import { cn } from '@/utils/cn';

const getGradientBackground = (

background: DocsConfig['background'],

color: string,

mode: 'light' | 'dark'

): { background?: string; className?: string; children?: ReactNode } | void => {

switch (background?.decoration) {

case 'gradient':

return {

background: `radial-gradient(49.63% 57.02% at 58.99% -7.2%, rgba(${convertColorsToRgbWithCommas(

color

)}, 0.1) 39.4%, rgba(0, 0, 0, 0) 100%)`,

className: 'h-[64rem]',

};

case 'grid':

return {

// -- snip --

The source files were just. There. Admittedly, the output was messy: interesting files were generally split between three folders with some duplicates between them, but it was a start. After combining those folders, putting them in a Next.js application, and sorting out some issues, we had a working Mintlify client that we could use to build a static site.

It was a starting point, but I wanted to automate this process so we could stay abreast of Mintlify’s frequent updating.

Post-prototype

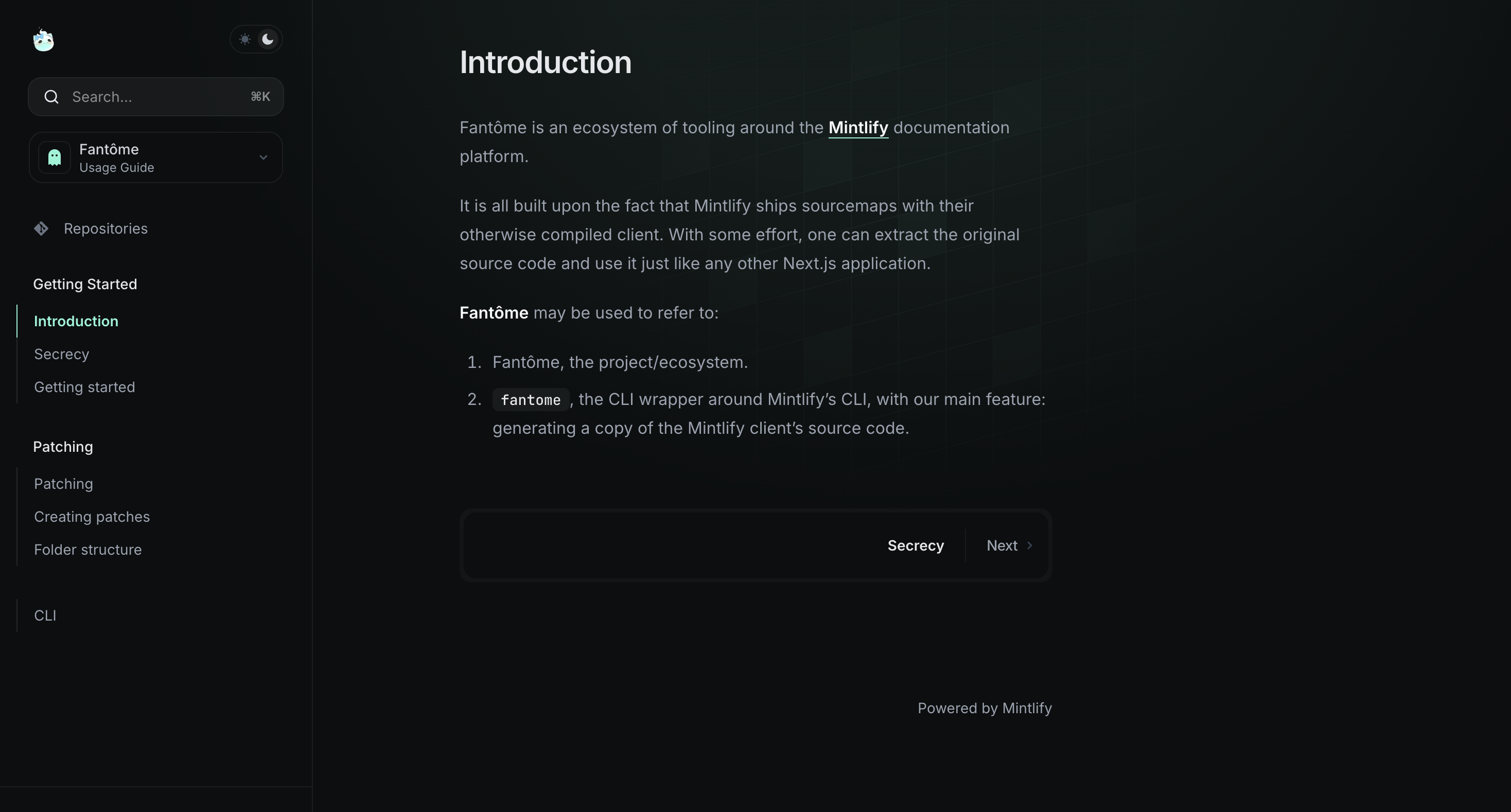

Since it was clear we were going in for the long haul, we needed a name. I floated Fantôme, after VTuber Mint Fantôme, and Alyxia was immediately on board.

I worked on a library for pulling a client tarball from their CDN and setting up a fully functional Next.js project around it. Notably, this included a partially-automated Tailwind config generator. By examining the compiled Tailwind CSS that the Mintlify client shipped with, it could determine what config changes they had made to their Tailwind Typography plugin and insert those into our local Tailwind config (though many other values in it were manually specified).

This “core” library powered the Fantôme CLI, a simple wrapper around Mintlify’s own CLI with additional features, such as downloading, building, and patching the client. The patching used a bespoke plaintext patching format and library I made, with support for line-independent patching, compiled/minified code modification, and automatic patch generation. It was the product of long, heavy discussions and musings with Alyxia, as we felt that regular unified diffs wouldn’t work well with the ever-changing Mintlify client.

Alyxia herself handled a lot of the infrastructure work. She set up an automated process to run Fantôme on the latest Mintlify client and store the result in a Git repo so that we could watch how the client evolved over time, alongside a Discord bot to DM her when the published version changed. She set up the documentation infrastructure, automatically pulling our documentation repository, rebuilding it with Fantôme, and deploying the published version:

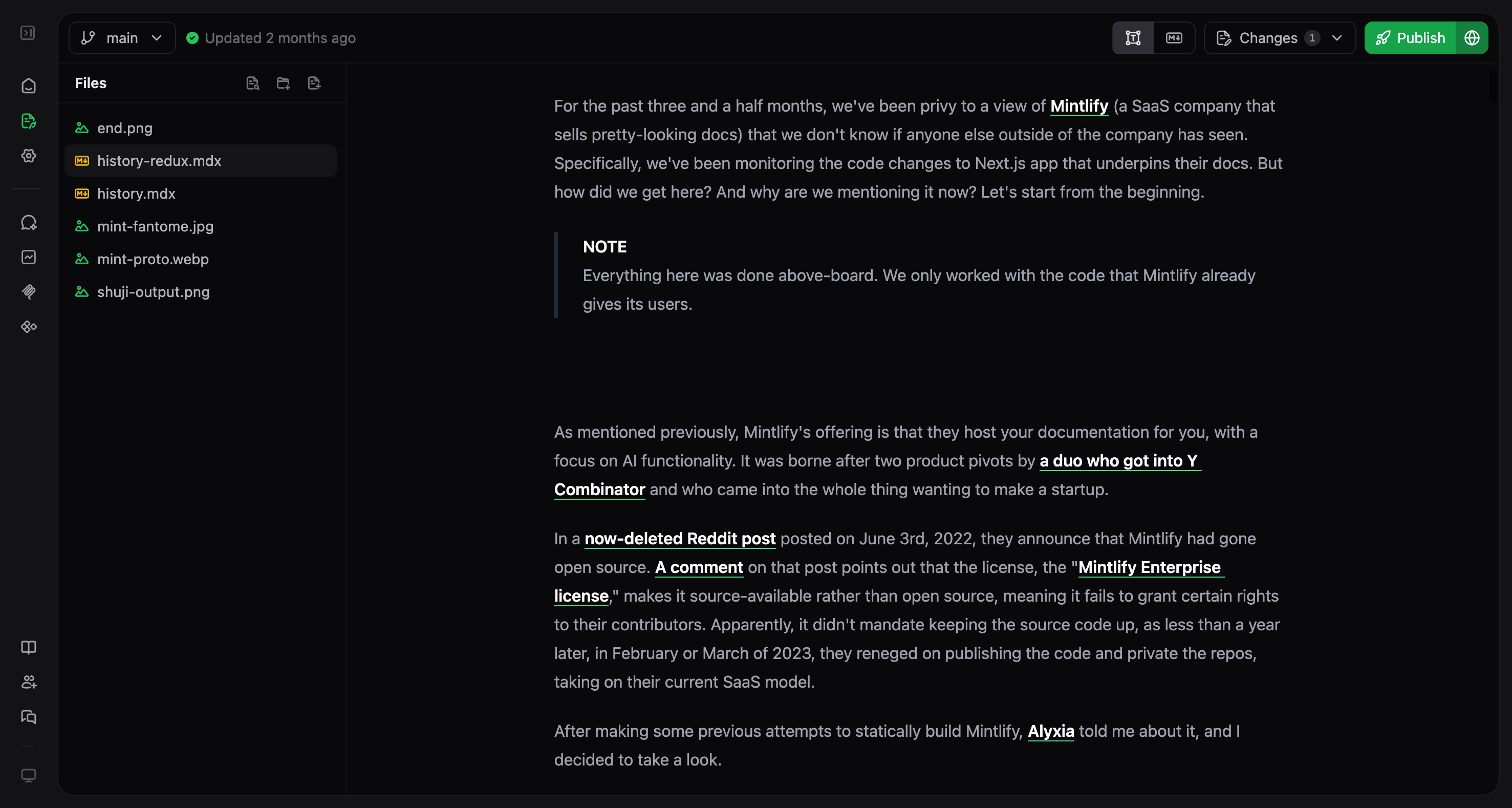

A tool she made that never saw use was the tarball downloader, a small script to download all published client tarballs into a local directory.1 She also embarked on an experimental effort to repurpose the editor Mintlify has in their dashboard for standalone use—a previous iteration of this post was written with it:

Exciting stuff, no? I was working on a “repository” system for publishing and consuming patches when, out of nowhere,

The End

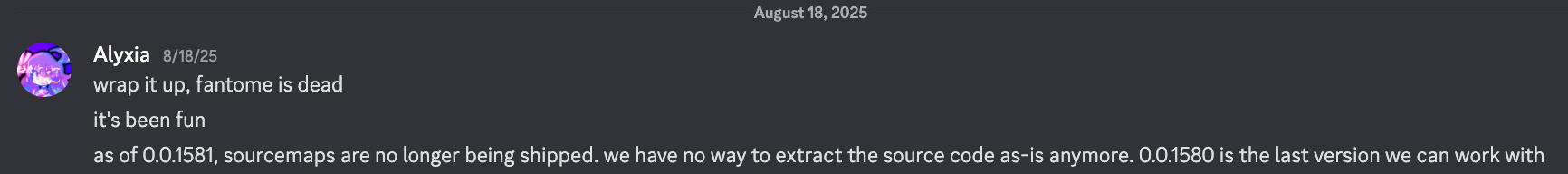

For whatever reason, Mintlify stopped shipping sourcemaps in their client tarballs, and there wasn’t anything we could do about it. We always knew this was going to happen sooner or later (hence why we kept all of our work secret); Mintlify’s whole business model is that they keep their source code from you, so we couldn’t simply contact them and ask if we could regain access.

Fantôme was dead.

So. What now.

Well, Mintlify keeps the tarballs for previous versions of the client uploaded on their CDN, so you can still use Fantôme with older versions that still shipped the sourcemaps (0.0.1580 and below). However, a lot of the work done on Fantôme was to keep up with the newest client releases, which is now pointless.

Note

Fun fact: The Mintlify CLI itself actually seems to support using older client versions with thedevcommand (internally, the flag’s description says it’s for CLI testing purposes), but the functionality isn’t mentioned in the help menu:mint dev --client-version <version>

We decided that the best way forward for Fantôme was to pull the latest working client version and all relevant Mintlify npm packages into a monorepo and start treating it as a regular Node.js project, but by that point, our interest in the project had petered out. As it stands, the initial steps to make a monorepo have been taken, but the repository lies dormant and unfunctional.

Will Fantôme ever be open sourced? Probably not. However, the library I wrote code patching is usable outside of Fantôme, and it was always my goal to eventually publish it as a standalone package. That library may eventually see the light of day.

Colophon

This post was originally far longer, documenting the technical work we had to do step-by-step. However, for the sake of brevity (and to actually get it out the door—it’s been over a month since we’ve had to shutter operations), I’ve chosen to write more generally about the project. There are a lot of little details, technical and otherwise, left out here.

I’d like to thank Alyxia for her help and for roping me into this in the first place, for dealing with the infrastructure work, and for keeping me updated on the client changes and version shenanigans that Mintlify was up to (the boggart of 0.0.1326). Over the course of Fantôme’s lifespan, the version archive swelled to a formidable 373 versions (roughly). Alyxia shepherdessed it through all of that, manually reconciling missing versions when needed, and for that I am incredibly thankful.

Fantôme ran for nearly three-and-a-half months, and I personally poured around 170 hours into it. It’s a project I’m very proud of, and, despite its untimely end, I’m glad I was able to work on it.

Footnotes

-

One of the design decisions we made was to not be reliant on our own infrastructure, and this tool would allow anyone to spin up their own archive. It was also part of what inspired the finished-but-never-merged-into-main “patch repository” system. ↩